Toyota Manufacturing Viability Calculator

This calculator helps you understand why Toyota exited the Indian manufacturing market. Enter your estimated costs and pricing to see if a car would be viable in the Indian market based on the article's key factors: price sensitivity, manufacturing costs, and volume requirements.

Enter Your Estimates

Market Context

Key Indian Market Facts:

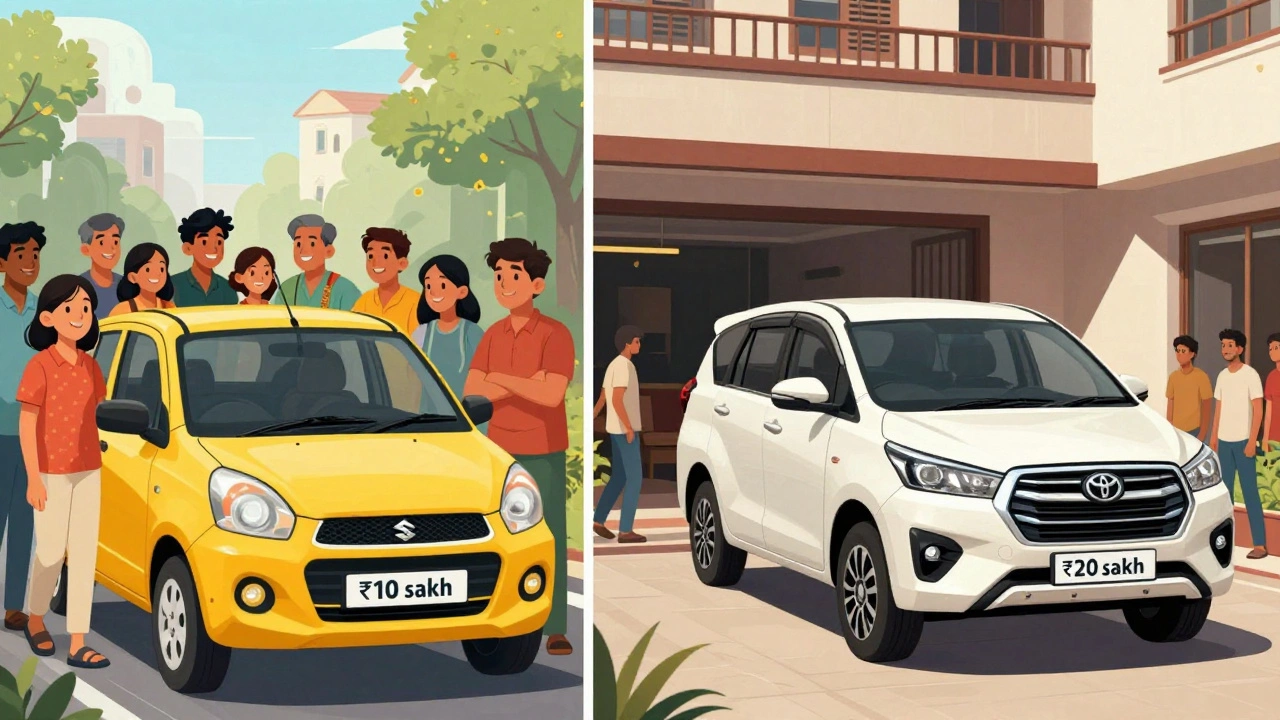

- 80% Over 80% of buyers spend under ₹10 lakh

- 5% Toyota sold 177,000 units (vs Maruti's 4M+)

- ₹6-7.5L Competitive segment (e.g. Maruti Swift)

- ₹15-20L Toyota's entry point was too high

Toyota stopped making cars in India in 2021. Not because sales were bad, but because the math didn’t add up. For over two decades, Toyota built cars in India with the same playbook it used everywhere else: build reliable, fuel-efficient vehicles, sell them at a premium, and wait for the market to grow. But in India, the market didn’t grow the way they expected. The cost to make cars here was too high, and the prices customers were willing to pay were too low.

Toyota’s Long Game in India Didn’t Pay Off

Toyota entered India in 1997 with a joint venture called Toyota Kirloskar Motor. By 2020, they had sold over 1.5 million cars in the country. That sounds like success. But here’s the catch: most of those sales came from a small slice of the market - middle-class families in cities who could afford a Corolla or Innova. India’s car market is huge, but it’s also incredibly price-sensitive. Over 80% of new car buyers in India spend under ₹10 lakh ($12,000). Toyota’s cheapest model, the Koleos, started at ₹15 lakh. Their most popular model, the Innova Crysta, cost over ₹20 lakh. That put them out of reach for most Indians.

Meanwhile, competitors like Maruti Suzuki, Hyundai, and Tata Motors were selling millions of cars under ₹10 lakh. Maruti alone sold over 4 million vehicles in India in 2020. Toyota sold 177,000. That’s less than 5% of Maruti’s volume. Toyota wasn’t losing money on every car - they were making decent margins. But they needed volume to cover fixed costs: factories, R&D, dealerships, supply chains. With low volume, those fixed costs became a drag.

The Cost of Making Cars in India Was Too High

Toyota tried to build locally. They had two plants in Karnataka - one in Bidadi, one in Andhra Pradesh. But even with local production, their cars cost more than rivals. Why? Because they stuck to global standards. Their engines were imported in parts, their safety features were over-engineered, and their quality checks were stricter than what Indian buyers demanded. A Hyundai Grand i10 could be built for ₹6 lakh and sold for ₹7.5 lakh. A Toyota Etios, which was mechanically similar, cost ₹8.5 lakh to make and sold for ₹9.5 lakh. That meant Toyota’s profit per car was higher, but their sales volume was a fraction.

Indian suppliers weren’t ready to deliver parts at the scale and cost Toyota needed. So they imported more components, which added import duties and logistics costs. Local suppliers focused on low-cost, high-volume parts. Toyota wanted precision-engineered parts with zero defects. That mismatch meant higher inventory, longer lead times, and higher costs.

Electric Vehicles Changed the Rules

By 2020, India’s EV policy was taking shape. The government offered subsidies for electric cars and charging infrastructure. But Toyota was slow to adapt. While Tata Motors launched the Nexon EV in 2020 and MG Motor rolled out the ZS EV, Toyota kept betting on hybrids. They brought the Prius and Corolla Hybrid to India - but they were priced above ₹30 lakh. That’s a luxury car price in India. Only a few thousand people bought them.

Toyota’s global strategy was to push hybrids as a bridge to EVs. But in India, hybrids didn’t make sense. Fuel prices were low, and the charging infrastructure was almost non-existent. Most buyers didn’t see the point in paying extra for a hybrid when a petrol car did the same job for half the price. By the time Toyota realized hybrids weren’t catching on, they were already stuck with high fixed costs and low sales.

India’s Market Wasn’t Ready for Toyota’s Model

Toyota’s success in Japan and the U.S. came from a simple formula: build durable, high-quality cars and charge a premium. That works when customers value reliability and resale value. In India, customers value affordability and low running costs. A Toyota might last 20 years, but if you can’t afford it in the first place, it doesn’t matter.

Indian buyers didn’t see Toyota as a status symbol like in the U.S. They saw it as an expensive option. Even the Innova, which was popular with fleet operators and families, was often seen as overpriced compared to the Mahindra XUV700 or the Maruti Ertiga. Toyota’s brand image didn’t translate. In India, “reliable” didn’t mean “worth the extra cost.”

They Left - But Didn’t Quit

Toyota didn’t walk away from India. They just stopped making cars here. In 2021, they shut down their manufacturing plants. But they kept their sales and service network alive. Today, Toyota still sells used cars, parts, and accessories in India. They also import a few high-end models like the Land Cruiser and the C-HR - but only a few hundred units a year. Their focus shifted from volume to prestige.

They also kept their R&D center in Bangalore, which works on global projects. And they still have a small team in India working on EVs and autonomous driving tech - but now they’re doing it as a cost center, not a profit center.

What Other Automakers Learned From Toyota’s Exit

Toyota’s exit sent a message to the entire auto industry: India is not a market you can enter with a global playbook. You have to build for India, not just sell to India.

Maruti Suzuki didn’t try to be premium. They made tiny, cheap, fuel-efficient cars. Hyundai built cars with bold designs and tech features that appealed to young buyers. Tata Motors used government subsidies to launch affordable EVs. All of them succeeded because they understood one thing: in India, price is the first filter. Everything else comes after.

Toyota’s mistake wasn’t bad quality. It was misreading the market. They assumed Indian buyers would pay more for reliability. Instead, Indian buyers paid less - and chose brands that matched their budget, not their ideals.

Could Toyota Come Back?

Maybe. But not unless they change everything. To return to manufacturing, Toyota would need to build a car under ₹8 lakh - something that meets Indian safety standards, uses mostly local parts, and is priced to compete with the Maruti Swift or Hyundai i10. They’d need to redesign their entire supply chain, cut their profit margins, and accept lower per-unit earnings.

They’d also need to invest in EVs. Right now, India’s EV market is growing fast. By 2030, over 30% of new car sales could be electric. If Toyota wants to be part of that, they’ll need to launch a ₹10 lakh EV - and make it cheaper than the Tata Punch EV or the MG Comet EV.

So far, they haven’t shown any signs of doing that. They’re watching from the sidelines, waiting to see who wins the budget EV race. If someone proves that a low-cost EV can be profitable, Toyota might jump in. But for now, they’re happy selling luxury imports and used cars.

What This Means for India’s Auto Industry

Toyota’s exit shows that global brands can’t just drop in and expect to win. India rewards local thinking. It’s not about having the best technology - it’s about understanding what people actually want.

Indian manufacturers now dominate the market because they built cars for Indian roads, Indian wallets, and Indian needs. Foreign brands that tried to bring their global models here failed - unless they adapted. Toyota didn’t adapt. They held on to their global standards too long.

The lesson? In India, you don’t sell your best product. You sell the right product at the right price. And if you don’t get that right, even the most reliable car in the world won’t save you.

Why did Toyota stop manufacturing in India?

Toyota stopped manufacturing in India in 2021 because their cars were too expensive for the majority of Indian buyers. Despite strong brand reputation, low sales volume made their high fixed costs unsustainable. They couldn’t compete on price with local brands like Maruti Suzuki and Hyundai, and their hybrid strategy didn’t resonate in a market with low fuel prices and poor EV infrastructure.

Did Toyota lose money in India?

Toyota didn’t lose money on each car - they made decent profit margins. But with only around 177,000 cars sold in 2020, they couldn’t cover the fixed costs of running two factories, a large dealership network, and global-quality supply chains. Low volume turned a profitable product into an unprofitable operation.

Is Toyota completely out of India?

No. Toyota still sells used cars, imports a few luxury models like the Land Cruiser, and maintains its service centers and parts network. They also keep a small R&D team in Bangalore working on global projects. But they no longer manufacture cars in India.

Could Toyota return to manufacturing in India?

Yes, but only if they build a car under ₹8 lakh using mostly local parts and compete directly with Maruti and Hyundai. They’d need to cut margins, simplify features, and invest heavily in EVs. So far, they haven’t shown any sign of doing this.

What’s the biggest lesson from Toyota’s exit?

The biggest lesson is that global brands can’t succeed in India by importing their existing models. Success comes from building cars that match local budgets, driving conditions, and consumer priorities - not from pushing premium features or global standards.

Toyota’s story in India isn’t about failure. It’s about misalignment. They built the right kind of car - just not for the right market.